London-based studio Procter-Rihl Architects has designed the Slice House project.

Completed in 2003, this 2,260 square foot, two story, contemporary home is located in Porto Alegre, the capital and largest city in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Slice House by Procter-Rihl Architects:

“Multi-Cultural Identity – Hybrid of Brazilian and British Culture

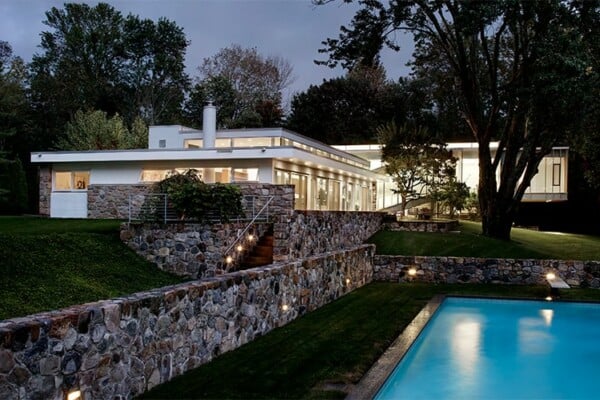

The project is a hybrid of Brazilian and British concerns. Although the building makes reference to Brazilian modernist architecture, its form takes a more contemporary European interest in asymmetrical complexity. Brazilian elements are the implementation of local concrete engineering, open plan typology, large extrovert spaces, swimming pool, outdoor living and lush garden flora. Concrete is not used in a typical Brazilian grand engineering gesture or sculptural form, but something more discrete. Thin continuous reinforced concrete structural walls bridge over the long slot windows and garage bay, but are not expressed as beams and disappear within the skin of the building. The diagonal concrete stair beam, which angles down to support the cantilevered corridor also disappears into a wrapping ribbon line, which flows around the courtyard.

Brazilian rawness comes through using materials such as timber formed poured concrete whereas British precision is a by-product of modular steel component construction. The building skin reflects these two halves. The steel front facade cladding, roof, gutters and grillwork is all detailed in a British way. Other British elements are the structural glass of the pool, attention to detailing and the use of Brazilian plants in a less formal natural layering common to British landscaping.

Spatial strategy, complex geometries and illusion

The project was conceived as a SLICE built on an urban residue leftover after the opening of a new road on the west side of the site. Space is defined by a series of non-orthogonal design decisions. The space folds and unfolds within the prismatic form. It develops a series of spatial distortions, which create an illusion of greater space on this narrow plot. A series of tilted 70deg walls extend the spaces where the eye of the beholder is displaced to further planes achieving an illusion of a larger space. The tilted ceilings create forced perspective also distorting the spatial perception. People are accustomed to perceive and understand orthogonal spaces. In a more complex geometry, the eye tries to understand the space and is constantly defied by it. The space becomes richer as the user perceives conflicting information from different viewpoints.

Instead of neutralising the linear site, Procter-Rihl decided to work with it. Entering at the small end, most of the site is a continuous open space for the social areas and inner courtyard. This long space contains the 7m continuous furniture component used as dining table, kitchen counter, and garden table. One long space gives unexpected depth to a domestic environment. In such a space, visual perception tends to tunnel in making the space appear to be smaller, but as the site is non-orthogonal increasing in width from 3.7 to 4.8m perspective is neutralised. This condition creates the illusion as if the space is bigger than it actually is. The three cross walls; front entrance, glass courtyard and bedroom are all angled 20deg off of the expected perpendicular. This elongates them and fools the eye into thinking the site is wider. The height of the main space, the upward flowing stair, and the open courtyard beyond open the space further.

The upper floor concrete ceiling folds up or down defining different spatial qualities. The stair arrives at the landing in a very open high zone. The ceiling slopes down in the corridor ahead to a very intimate 2.1m height at the bedroom door. This puts the corridor into a forced perspective, which makes the private area of the house appear further away from the social areas. Turning up the stair and moving to the guest room/ pool lounge the ceiling continues a slope up opening out to the pool terrace and sky. The bedroom ceiling folds up from its low point at the door opening the space visually above the dressing unit furniture pieces to the bath beyond. The bedroom is enlarged visually while remaining a separate piece from the front public section of the house.

Swimming as an event – the voyeur experience

The swimming pool, located on the upper floor, is the main event generator in the space. It polarises the attention in the house where the users are all voyeurs in the space, making homage to the body, a national obsession. The pool is structurally supported by the sidewalls and thus is a floating block above the living space. During the day it works as a daylight filter creating different rippled water effects as the day progresses. At night with the pool lights on it works as a large coloured light fitting.

Building technology and generation of complex spaces

In the last decade in Europe, the educational system and architectural publications have overemphasised the digital medium ignoring the craft side of the building process. Digital media and modelling are important and useful in conceptualising design and detailing but the translation through craft is ultimately more important than virtual spaces. Procter-Rihl prefers to engage in the physical creation of complex structures or spaces. Furniture and exhibition work has enabled the practice to pursue this type of experimentation more easily.

The project uses prismatic geometry with flush details, which demands more careful detailing, and site supervision. Remodelling in 3d allowed adjustments to ensure accuracy and precision of delivered components with final sizing on site. A more complete prefabrication or factory production of assemblies was not possible or available in Brazil. Windows, metalwork, and cabinetwork were assembled to fit onsite. These elements were crafted precisely in contrast to the intentionally rough concrete surfaces.

A wood formed cast concrete was preferred since it is a local tradition and precast concrete or metal formwork is not generally available for this size of a project. The wood formwork was built in situ with a plank pattern emphasising wood grain, accidental texture pattern, and imperfections. The ceilings were cast at a slope angle of 10 degrees, a familiar technique in the Brazilian building process. The terrace and swimming pool employ an in situ technology of resin and fibreglass coatings applied on site after the concrete cured completely. This technique reduces the number of materials meeting around the pool waterproofing and allows customising the shape and size of the pool. The final concrete finish floor was a screed laid over a thick plastic layer on the concrete slab to allow movement. This screed was machine polished and sealed for a shiny finish.

Probably the best feature of the house is the crafted metal work. The 7m-kitchen counter is a continuous steel slab with 2m-cantilevered tables floating off of both ends dining and courtyard sides. The thick steel plate folds up transitionally between the lower dining height and higher work counter. A made to fit stainless steel sink has been inserted into the triangle transition underneath. The steel work surface is coated with avocado coloured two part catalysed laboratory paint providing an extremely hard finish. The stair is 8mm steel plate accordion folded and welded in sections onto the undercarriage beam plates. The 8mm thin edge is emphasised in light grey contrasted with the exposed underside painted in a deep aubergine purple. Because the stair is a “U” shape with offset forces the British engineers were able to design thinner and lighter balustrade details than normal. The thin 32mm upright tubes support and 35mm handrail, which forms a looped continuous top handrail and lower thigh height bottom rail. The balustrade leans out with the handrail atop the upright and an ankle height rail pulled in giving a sensation of safety to the open balustrade. The complex 3d shape of this balustrade was digitally visualised for preliminary component bending and cutting with final curve refinement done on site. The skilled Brazilian welder sliced and re-welded some curves to finish the railings. The curves were not in the same horizontal or vertical planes and were ascending diagonally up the stair.”

Photos by: Sue Barr, Marcelo Nunes